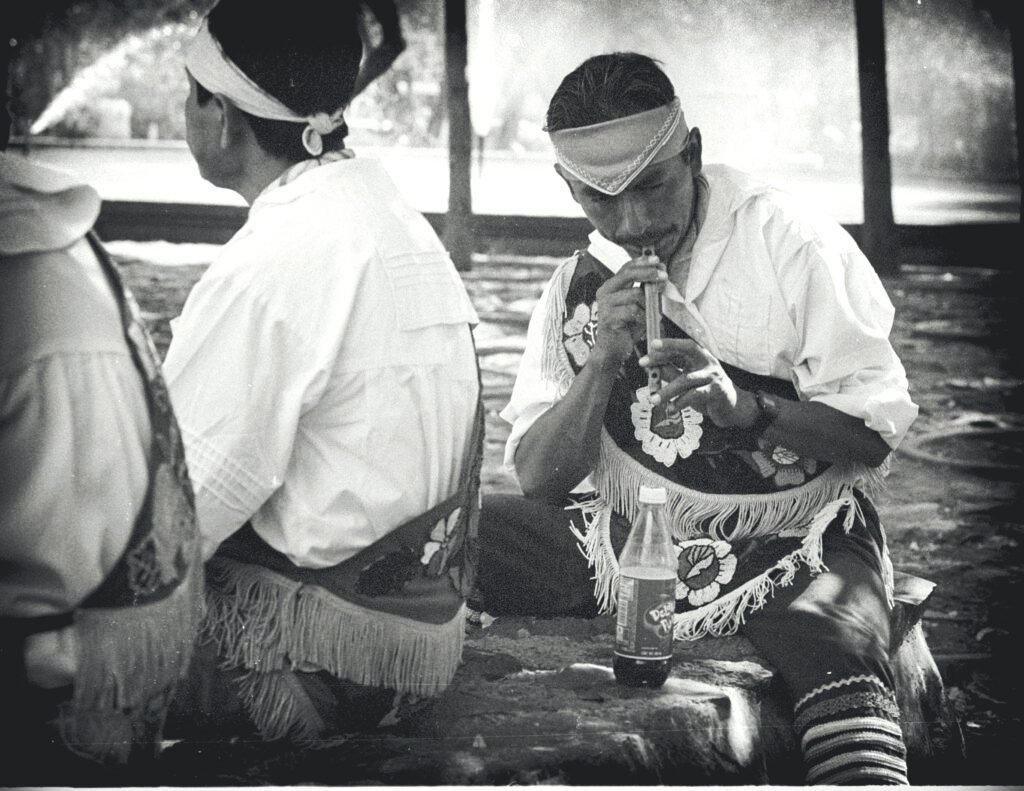

Beneath the shade of a ceiba tree near the edge of the plaza, where dust rises gently with the hush of late afternoon, a volador squats on a bench, his red trousers dusty, his embroidered shirt half-unbuttoned, his headdress resting beside him like a crown laid down with care.

He holds a reed flute, softly playing a tune that drifts like a feather through the air—a song older than tourists, older than the plaza, older than roads. Around him, the others rest: one sharpening a wooden pole, one sipping water from a plastic bottle, one lying on his back, hat over his face, breathing slow and even.

But the one with the flute—Mateo, twenty-nine, Veracruz-born, Nahua-blooded—plays on, fingers dancing over the worn holes, calling to the wind, to the gods, to the earth that still listens.

It’s not a performance now. There’s no crowd. No applause. Just rhythm and dust and sun.

A child watches quietly from the curb. An old woman nods in recognition. Even the pigeons seem to pause. The flute sings of flight, of rope spun from trust, of men becoming birds in honor of rain.

Later, he will climb the pole again—spin and fall with grace, feet in the sky, heart in the wind. But now, he is still. Still flying. In sound.