She is called Bà Tám, though no one remembers if that is her real name. In these parts of the Mekong Delta, names blur like the riverbanks after the rain—what matters is that she’s still here. Sixty, maybe more. She stopped counting when her husband was swallowed by a typhoon thirty-six floods ago.

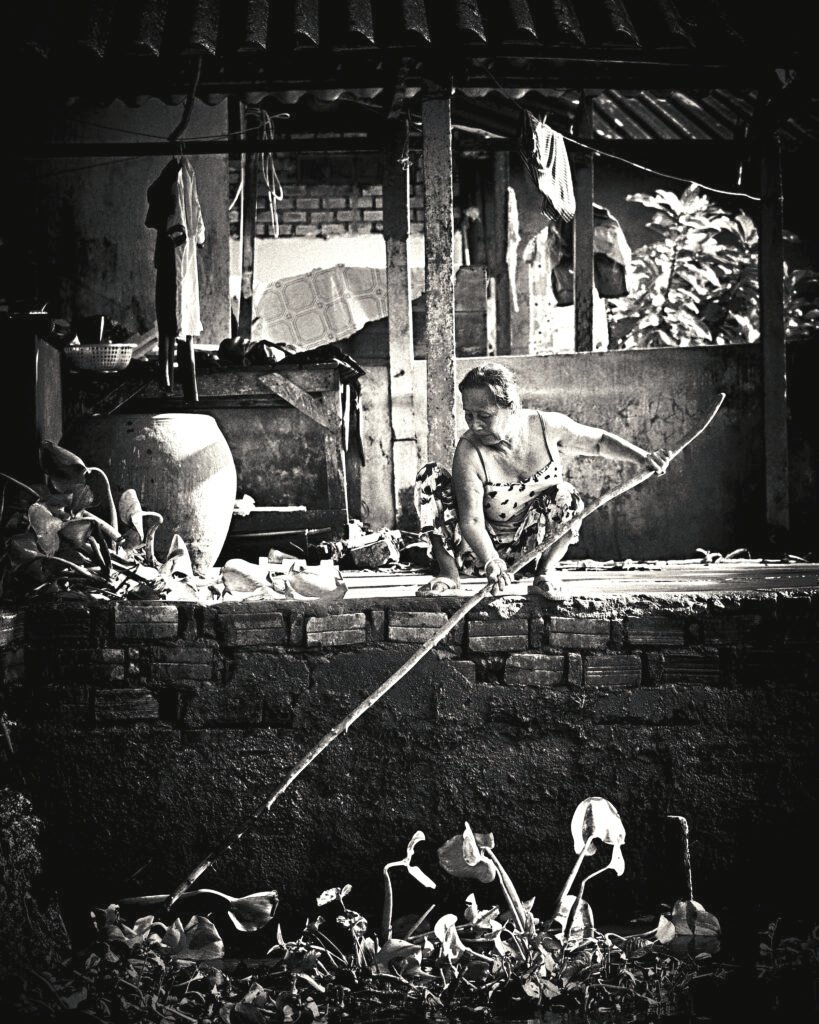

Her house is a thatched lean-to stilted just above the highwater line, patched with old rice sacks and election posters. The wooden floor creaks like old bones. One wall leans slightly where the termites won their quiet war. From her hammock, she watches the river like it’s an old lover she never truly forgave.

Each dawn, she boils water over a clay stove, the fire coaxed from coconut husks and memory. She drinks tea with no sugar. No teeth left. Eats rice crust and dried fish if she has it. If not, just tea and a story to herself.

“I was beautiful once,” she says to no one in particular, adjusting the scarf that hides the burn scars across her neck—souvenirs from a napalm sweep when she was barely a bride. She remembers running with her infant son through the mangroves, pressing his face into her chest to keep the screams down. He died before he turned five—from cholera, from mud, from fate.

She speaks to him still, sometimes, when the river is quiet and the boats are gone.

“Con ơi, mẹ chưa quên con đâu…”

“My son, I haven’t forgotten you.”

Tour boats pass now—long, lacquered things with foreigners who wear sunglasses even when the clouds are thick. They point cameras at her like she’s part of the landscape. Sometimes, she waves. Sometimes, she doesn’t. They never stop.

Once, a young tourist tossed her a small packet of Oreos wrapped in plastic. She opened it carefully, as if it might be medicine, or a trap. She ate one, saved the rest. Shared them later with the skinny dog that sleeps under her house when the tide is low.

She weaves mats in the afternoon. Not for money—no one buys anymore—but because her hands forget how to be still. Her fingers are twisted with arthritis, her spine bowed, but the mats come out tight and straight. Sometimes she gives one to a passing fisherman. Sometimes she burns them for warmth.

When the river rises, she does not run. She stacks her pots, raises her mattress, waits it out with a calm that can’t be taught. The Mekong has taken everything it could from her already. What more could it want?

At night, she listens to the frogs, to the wind in the nipa palms, to the ghosts of old songs carried on mosquito wings.

She is not a saint. Not a symbol. Just a woman the world forgot—except the river, which remembers everything and nothing.

And still, each morning, she wakes.

Boils tea.

Looks out at the brown water.

And whispers,

“Chưa xong đâu…”

“Not finished yet.”