He stands at the Nile’s edge in Luxor,

barefoot in tattered shorts,

a striped shirt faded by sun and salt,

watching the felucca sails flutter like paper wings in the wind.

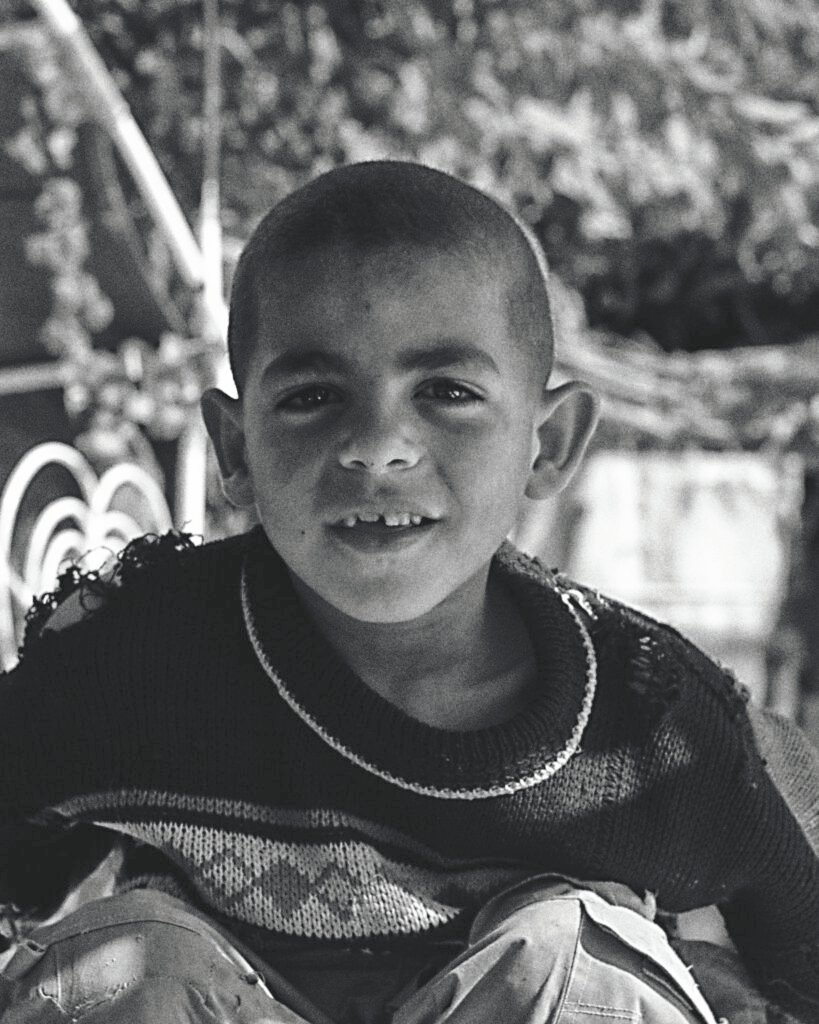

Khalid, eight years old.

Son of a boatman.

Grandson of the river.

His father, tall and lean with hands like rope, guides a wooden felucca named Layla across the slow breath of the Nile, carrying tourists who ask for “sunset rides” and photos with ancient light behind them.

Khalid stays on shore, waiting.

His sandals broke last Ramadan. His shirt hangs off one shoulder.

But he wears his father’s old watch on his wrist—

stopped at 3:17, but precious,

proof that he is not just a boy,

but a boatman’s son.

He doesn’t beg.

Not quite.

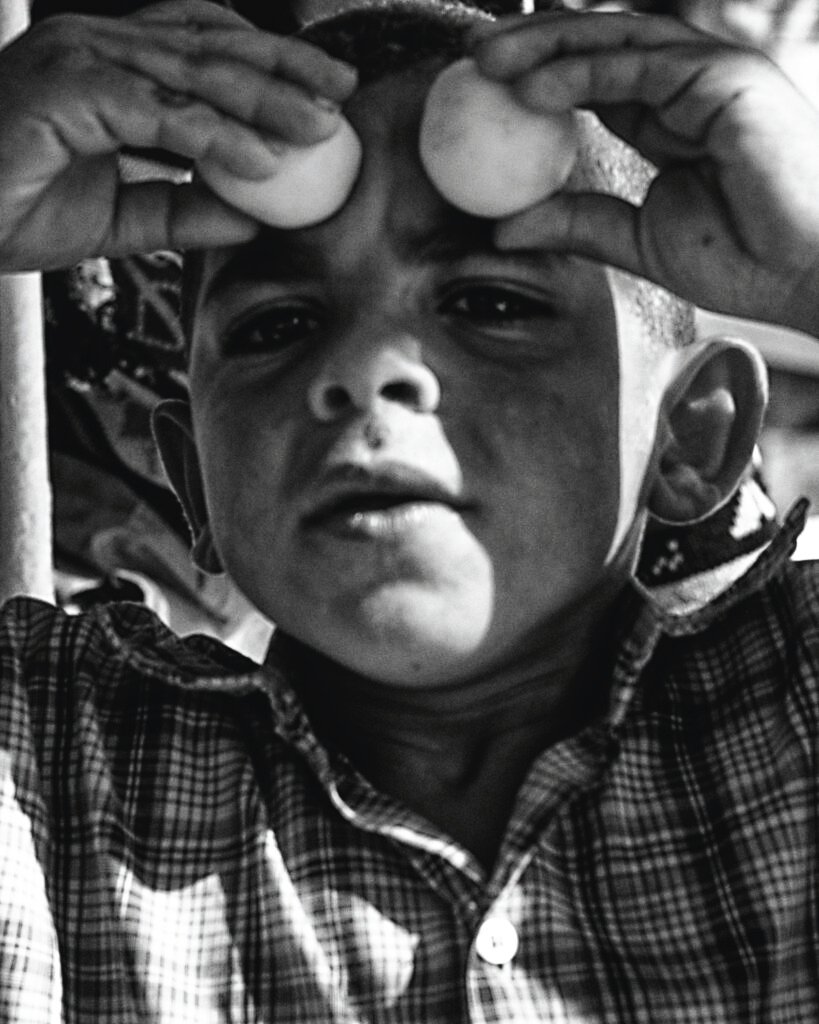

He offers trinkets: scarabs carved from soapstone, bookmarks with hieroglyphs, a smile too practiced for a child.

“Only ten pounds, habibi. Real Egyptian!”

he calls out in a voice half-sand, half-song.

Some buy. Some wave him away.

He shrugs. Swats a fly. Waits for the next sail to drift in.

Sometimes he helps tie the ropes,

hands moving fast like his father’s,

pulling the hull against the dock with all his small weight.

Other times, he just stares across the river at the banana trees and cracked tombs,

wondering what the pharaohs would think of him,

thin and brown and tired before dinner.

At night, when the feluccas sleep like tired birds,

he curls beside his father on the deck,

blanket to blanket,

listening to the creak of wood and the hush of water.

“One day,” his father whispers,

“this boat will be yours.”

Khalid nods, eyes wide in the dark.

He is already ready.

Already river-blood.

Already stitched into the wind and canvas of Egypt.