In the red dust of a village near Battambang, just past the rice paddies and the rusted road signs, sits Vannak, thirty-three, his left pant leg tied neatly at the knee, baring his prosthesis, a crutch laid beside him like a silent companion.

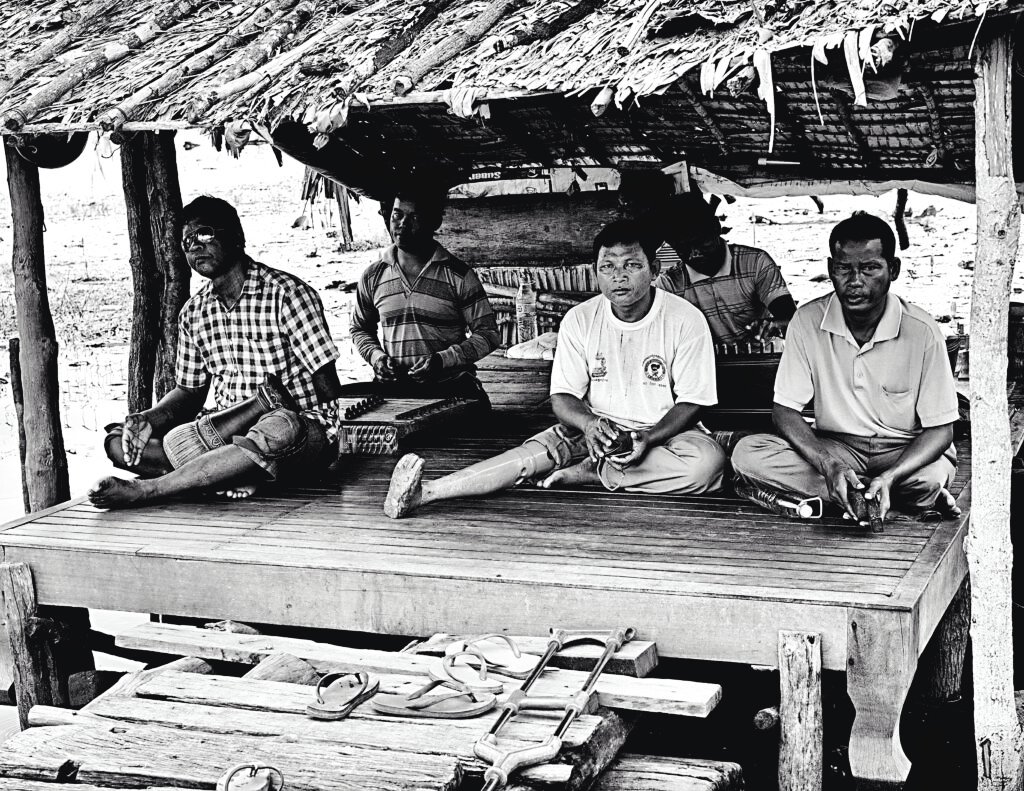

He lost the leg in 1998. A landmine, hidden in the field his father once farmed. He remembers the pop. The light. Then the silence—like the whole world took a breath and never gave it back. But now—years later—he’s not sitting in sorrow. He’s crouched beneath a lean to hut, laughing with three friends and sipping cold sugarcane juice from a plastic bag, his eyes sharp, his spirit louder than the cicadas.

Chenda, his best friend since boyhood, nudges him with an elbow: “You still can’t dance. One leg, no rhythm.”

Vannak grins: “Better than you. Two legs, still stiff like buffalo.”

The group roars. Nearby, a boy—his nephew—kicks a deflated soccer ball. Vannak cheers him on, slaps his crutch like a drum.

In the afternoons, he repairs old radios. Makes small money. Sometimes paints signs for shops—his lettering slow but proud. His friends help when he needs to cross muddy fields. He fixes their broken umbrellas. They bring him mangos. They all carry each other in different ways.

He says the leg is gone, but the joke is still there. The fight is still there. Sometimes, he straps on a an old prosthesis. Not to hide the fact that he is an amputee–it;s just easier to walk. To show his niece he can still ride a bike. To get to the market before the price of fish goes up again.

When foreign visitors come to the village, some look at him too long. Some offer money. Some look away. He’s used to that. He doesn’t need pity. He needs respect—and a cold drink, and a good story, and friends who know his nickname from school.

He lost his leg to a war he didn’t start. But he kept his hands, his voice, and his place in the circle. And that, as Vannak says, “is more than enough to stand on.”