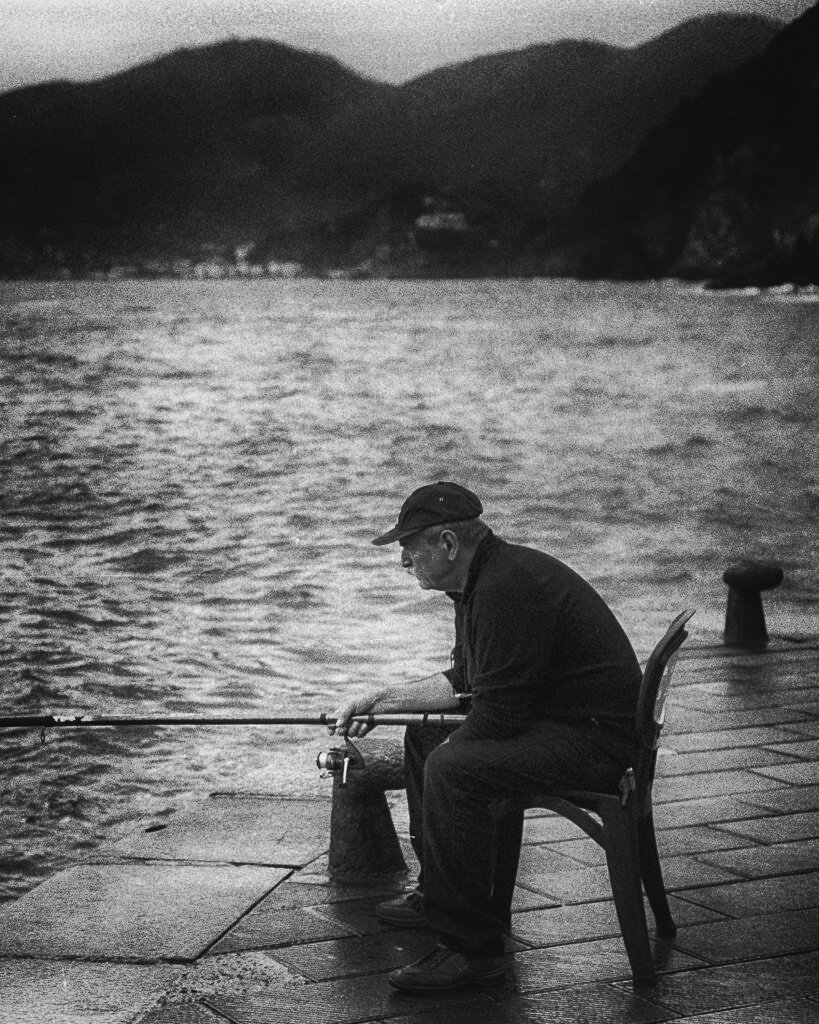

He sits on a plastic chair at the edge of Manarola, where the cliffs meet the sea with no apology, a rod balanced in his hand and time dripping slow like saltwater down stone. The locals call him Gianni, though no one’s sure if that’s his real name. He’s somewhere in his seventies. Lean as driftwood. Eyes like polished glass—blue, but faded, like old postcard ink.

Every morning, just after sunrise, he climbs the stone steps barefoot, line over shoulder, bait in a jar: leftover anchovies, crushed garlic, olive oil. “My secret weapon,” he once joked to a passing child.

“Smells like heaven, tastes like old boots.”

He casts without flourish. No sport in it. Just patience. No bucket, either. Just a cloth sack. He takes only what he’ll eat, maybe what he can trade for a tomato or two. Behind him, the pastel houses of Cinque Terre lean into each other like gossiping old friends. Tourists snap selfies on the overlook. Lovers sip Aperol and point at the sea. Gianni barely notices. He listens to the gulls. To the waves muttering secrets in Ligurian dialect.

Once, they say, he owned a fishing boat—La Rosetta—named after a wife who died too young. He sold the boat. Kept the memories. And the sea? The sea kept him.

Sometimes a local boy joins him, asks questions. “Why fish here?”

Gianni shrugs. “Because the sea still remembers me.”

When the sun gets high and the tourists start filling the piazza, he reels in the line, slow and silent. A small silver fish dangles, gleaming. He nods, as if to say: Still here. Still mine.

Then he packs up, barefoot down the rocks, past the gelato shop, past the mural of fishermen long gone,

his sack swinging, his shadow long. And Cinque Terre carries on—bright, busy, alive—while one old man and the sea share their quiet, like a story neither of them is finished telling.